Final Rating: 4/5

Marie Celements is back at the Vancouver International Film Festival, her latest film Bones of Crows opened the 41st edition of VIFF to a sold out crowd at The Centre for Performing Arts. Her last film, Red Snow, played the festival and won the prestigious Most Popular Canadian Film award and it wouldn’t be a shock to see Bones repeat the feat. The film is a non-linear tale that shows the intergenerational trauma the country and institutions of Canada have inflicted upon the Indigenous peoples who were here with vibrant cultures and societies long before colonizers forced themselves onto the land. The story follows Aline Spears, a Cree woman from Manitoba, as we get to see the entire journey of her life from Residential School victim, to translator during WW2 for the Canadian military, to mother trying to raise her two children with a husband who gets thrown aside by the government after serving in the war, to an elder fighting the Catholic Church to recognize and apologize for the sins they committed in ruining countless Indian lives.

The film consists of three timelines with Aline Spears being played by Summer Testawich, Grace Dove and Carla-Rae at different parts of Aline’s life. Young Aline and her three siblings live a happy life with their loving parents, until the police and local priest come knocking on the door to take away the children to the newly formed Residential Schools. Their parents face the option of signing over their children to the Church, or go to jail and presumably that the Government would then take control of the children and then force them into the Residential Schools, not giving their parents much of a choice. We see the prison-like conditions of cramped sleeping quarters, forced prayer, and Josef Mengele-like experimentation with diet and nutrition. We see the sexual abusers at work and the physcial violence inflicted upon the children, cruelty that when evoked during international conflicts gets labelled as war crimes with accompanying punishments for these crimes. Except these perpetrators got promoted and honoured.

After finally getting out of the Residential School system, Aline’s only option is to join the military, first as a morse code operator, before being brought in as a Cree Code Talker, a secret branch of the military that would encrypt messages into Cree and translate incoming Cree relays into English again. The Americans had a similar program with Navajo people, as seen in the John Woo film Wind Talkers, the Germans were unable to crack either the Cree or Navajo languages since they used slang that would only be understood by native speakers. Here in the military Aline would meet her future husband Adam Whallach, played by Phillip Lewitski, who quickly becomes disillusioned with the promises the Canadian government is making to Indian enlistees. He is proven correct post war when despite getting injured while fighting for his “country”, finds out that by joining the military he renounced his Status Indian claim but doesn’t get to become a Canadian citizen, which means that the military doesn’t have to pay him a pension or offer benefits. The couple start a family, but with Adam unable to work he becomes an alcoholic and Aline only able to get work as a cleaner and a caretaker for the elderly.

Lastly we meet the elder Aline as she is heading to Vatican City to meet with a delegation from the Church as they prepare to acknowledge their involvement with Residential Schools (but not fully admit their wrong doings). Aline and her now adult daughter Taylor Whallach, played by Gail Maurice (who wrote and directed ROSIE also seen at VIFF) plan to speak at the ceremony in an attempt to force the Church to accept responsibility for their heinous actions. This gives Aline the opportunity to actually face one of her former abusers from the Residential School system and allows her to receive some relief that he might finally face some consequences.

The film constantly shifts between the different timelines, unfolding in a complicated manner, showing us after effects and trauma first then going back in time to reveal what the original root cause was. Early on we see adult Aline with a scar on one of her hands, when she joins the military they offer to surgically repair her hand. It isn’t until near the end of the film that the physical reminder of her time in the Residential School system was orchestrated by a nun who broke multiple bones in her hand after an attempted escape and where Aline would receive subpar medical care leaving the lasting marks of the abuse.

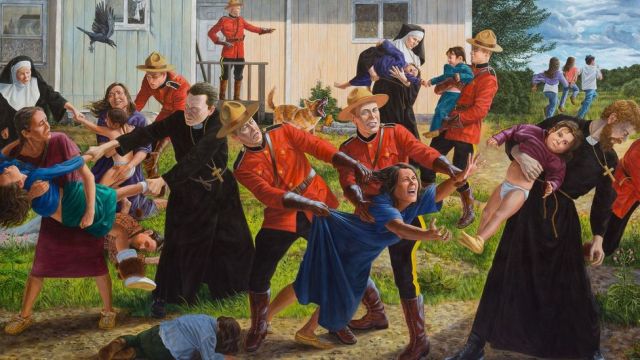

Clements is a maestro with the camera and she inserts plenty of shots inspired by art and photography. We get a prologue scene showing early colonizers being cruel to the locals in an attempt at an April Fool’s joke. The vignette is shot in black in white and features an impressive mountain of bison skulls, recreating the famous photograph showing the mass culling colonizers did to the local animal population. When Aline’s father is forced to sign over his children to the Church, the scene plays out like a Kent Monkman painting with the Church and State force themselves upon the Indigenous communities and use the police as force to remove them, leaving parents screaming and crying for their children. When Aline and her siblings attempt to escape their Residential School, they are trudging through the snow, cold, starving and unsure where to go in a way that is reminiscent of the Chanie Wenjack story, immortalized by the late Gord Downie.

The film is inspired by true events and uses the history of the victims and survivors of abhorrent policies and abuses to thread a story centered around one family. Not every Indigenous family had children die at Residential Schools, or had their status taken away, or were affected by the disproportionate amount of women who went missing or were murdered, but they are common enough that it is neither inconceivable nor outrageous to show how one family was dealt so much intergenerational trauma. The film wears its politics on its sleeves, sometimes removing any chance of subtly to instead eschew an in your face attitude. The film works best when we are presented with harrowing imagery and tableaus where nothing is needed to be said to communicate the suffering inflicted upon this family and the scenes that are overwritten with direct addresses to the camera play out more like an after school special, like when an employer of Aline spews racist comments at her after Aline finishes taking care of her father, the two exchange snappy lines with a metaphorical slap to the face by Aline to win the conversation.

Since the film spans multiple generations there are plenty of actors who make the most of limited screen time, from Grace Dove as the adult Aline, showing a willingness to be optimistic in the face of continued adversity, or the child actors who play the young Spears clan; Summer Testawich, Sierra Rose McRae, Payne Merasty and Ava Ahn Le as Aline, Perseverance, Tye and Talia who show the utmost stoicism despite the torture that is inflicted upon them. There is also Jonathan Whitesell who plays Thomas Miller, who appears to be the only person to offer compassion in the Residential School by whisking Aline away from the day to day drudgery to give her piano lessons.

Clements has crafted an interwoven tapestry so unique and personal that it is bound to speak to plenty of people who suffered similar injustices, and a worthy watch for people that either refuse to learn about the Residential School system or for those that don’t understand the depths of pain and trauma that it still causes to this day. It was no more evident that in the VIFF opening night screening that audience members were moved to tears and a standing ovation that lasted the entire duration of the credits.

Bones of Crows was seen during the 2022 Vancouver International Film Festival. Thank you to the festival for a media pass.

Great post.